Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Roman gardens were greatly inspired by Greek gardens and were usually in the peristyles. Roman Gardens were indoor. Ornamental horticulture became highly developed during the development of Roman civilization.

The administrators of the Roman Empire (c.100 BC - AD 500) actively exchanged information on agriculture, horticulture, animal husbandry, hydraulics, and botany.

Seeds and plants were widely shared. The Gardens of Lucullus on the Pinion Hill at the edge of Rome introduced the Persian garden to Europe, around 60 BC. The garden was a place of peace and tranquility-- a refuge from urban life-- and a place filled with religious and symbolic meanings.

As Roman culture developed and became increasingly influenced by foreign civilizations through trade, the use of gardens expanded and gardens ultimately thrived in Ancient Rome.

Influences:

Roman gardens were influenced by Egyptian, Persian, and Greek gardening techniques. Formal gardens existed in Egypt as early as 2800 BC. During the 18th dynasty in Egypt, gardening techniques were fully developed and beautified the homes of the wealthy.

Porticos were developed to connect the home with the outdoors and created outdoor living spaces. Persian gardens developed according to the needs of the infertile land. The gardens were enclosed to protect from drought and were rich and fertile in contrast to the dry and arid Persian terrain.

Pleasure gardens originated from Greek farm gardens which served the functional purpose of growing fruit.

Uses of Gardens:

Gardens were not reserved for the extremely wealthy. Excavations in Pompeii show that gardens attaching to residences were scaled down to meet the space constraints of the home of the average Roman.

Modified versions of Roman garden designs were adopted in Roman settlements in Africa, Gaul, and Britannia. As town houses were replaced by tall apartment buildings, these urban gardens were replaced by window boxes or rooftop gardens.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

In practice, painters can eloquent shapes by juxtaposing surfaces of different intensity by using just color one can only represent symbolic shapes. For example, a painter perceives that a particular white wall has different intensity at each point, due to shades and reflections from nearby objects, but ideally, a white wall is still a white wall in pitch darkness.

Color and tone are the essence of painting as pitch and rhythm are of music. Color is highly subjective, but has observable psychological effects, although these can differ from one culture to the next.

Moreover the use of language is only a generalization for a color equivalent. The word "red", for example, can cover a wide range of variations on the pure red of the visible spectrum of light.

There is not a formalized register of different colors in the way that there is agreement on different notes in music, such as C or C♯ in music. For a painter, color is not simply divided into basic and derived colors (like, red, blue, green, brown, etc.).

Painters deal practically with pigments, so "blue" for a painter can be any of the blues: phtalocyan, Paris blue, indigo, cobalt, ultramarine, and so on.

Psychological, symbolical meanings of color are not strictly speaking means of painting. Colors only add to the potential, derived context of meanings, and because of this the perception of a painting is highly subjective.

The analogy with music is quite clear—sound in music is analogous to light in painting, "shades" to dynamics, and coloration is to painting as exact timbre of musical instruments to music—though these do not necessarily form a melody, but can add different contexts to it.

Monday, September 13, 2010

Wood entered the painting in a competition at the Art Institute of Chicago. The judges deemed it a "comic valentine," but a museum patron convinced them to award the painting the bronze medal and $300 cash prize.

The patron also convinced the Art Institute to buy the painting, which remains there today.

The image soon began to be reproduced in newspapers, first by the Chicago Evening Post and then in New York, Boston, Kansas City, and Indianapolis.

However, Wood received a backlash when the image finally appeared in the Cedar Rapids Gazette. Iowans were furious at their portrayal as "pinched, grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers".

One farm wife in danger to bite Wood's ear off. Wood protested that he had not painted a caricature of Iowans but a depiction of Americans.

Art critics who had favorable opinions about the painting, such as Gertrude Stein and Christopher Morley, also assumed the painting was meant to be a send-up of rural small-town life.

It was thus seen as part of the trend toward increasingly critical depictions of rural America, along the lines of Sherwood Andersen's 1919 Wines burg, Ohio, Sinclair Lewie's 1920 Main Street, and Carl Van Vechten's The Tattooed Countess in literature.

However, with the onset of the Great Depression, the painting came to be seen as a depiction of committed American pioneer spirit.

Wood assisted this transition by renounce his Bohemian youth in Paris and grouping himself with populist Midwestern painters, such as John Stuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton, who revolted against the dominance of East Coast art circles.

Wood was quoted in this period as stating, "All the good ideas I've ever had came to me while I was milking a cow.

This Depression-era understanding of the painting as a depiction of an realistically. American scene prompted the first well-known parody, a 1942 photo by Gordon Parks of cleaning woman Ella Watson, shot in Washington, D.C.

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

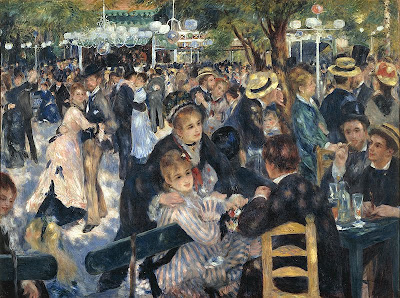

A core group of young realists, Claude Monet, Pierre-Augusta Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frederic Bazille, who had studied under Charles Gleyre, became friends and often painted together.

They soon were joined by Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, and Armand Guillaumin.

In an atmosphere of change as Emperor Napoleon III rebuilt Paris and waged war, the Academic des Beaux-Arts dominated the French art scene in the middle of the 19th century.

The Academic was the upholder of traditional standards for French painting, both in content and style.

Historical subjects, religious themes, and portraits were valued ,and the Academic preferred carefully finished images which mirrored reality when examined closely.

Color was sober and conservative, and the traces of brush strokes were suppressed, concealing the artist's personality, emotions, and working techniques.

The Academic held an annual, juried art show, the Salon de Paris, and artists whose work displayed in the show won prizes, garnered commissions, and enhanced their prestige.

The standards of the juries reflected the values of the Academic, represented by the highly polished works of such artists as Jean-Leon Gerome and Alexander Cabanel.

They were more interested in painting landscape and contemporary life than in recreating scenes from history.

Each year, they submitted their art to the Salon, only to see the juries reject their best efforts in favor of trivial works by artists working in the approved style.

In 1863, the jury rejected The Luncheon on the Grass by Eduard Mamet primarily because it depicted a nude woman with two clothed men at a picnic.

While nudes were routinely accepted by the Salon when featured in historical and allegorical paintings, the jury condemned Manet for placing a realistic nude in a contemporary setting.

Tajmahal Paintings

Painting Iteams

Creation of Paintings

Painting Equipments

Beautiful Rose Painting

Green Nature Painting

Canvas Painting

Pictute of Artist

Color Paintings

Online Paintings